1. Introduction

In the present information and knowledge era, knowledge has become a key resource. Faced with competition and increasingly dynamic environments, organisations are beginning to realise that there is a vast and largely untapped asset diffused around in the organisation – knowledge (Gupta, Iyer & Aronson, 2000).

This realisation not only occurs in business organisations but also in non-profit organisations such as academic libraries. The conventional function of academic libraries is to collect, process, disseminate, store and utilise information to provide service to the university community. However, the environment in which academic libraries operate today is changing. Academic libraries are part of the university and its organisational culture. Whatever affects universities also affects academic libraries. The role of academic libraries is changing to provide the competitive advantage for the parent university – a factor that is crucial to both staff and students (Foo et al., 2002).

Knowledge management is a viable means in which academic libraries could improve their services in the knowledge economy. This can be achieved through creating an organisational culture of sharing knowledge and expertise within the library. However, organisations face innumerable challenges in nurturing and managing knowledge. The challenges occur because only a part of knowledge is internalised by the organisation, the other is internalised by individuals (Bhatt, 2002). Organisations, including academic libraries can create and leverage its knowledge base through initiation of appropriate knowledge management practices. TFPL (1999) argued that “for organisations to compete effectively in the knowledge economy they need to change their values and establish a new focus on creating and using intellectual assets”.

The success of academic libraries depends on their ability to utilise information and knowledge of its staff to better serve the needs of the academic community. Lee (2000) pointed out that the knowledge and experiences of library staff are the intellectual assets of any library and should be valued and shared. Academic libraries as constituents of the parent university should rethink and explore ways to improve their services and become learning organisations in which to discover how to capture and share tacit and explicit knowledge within the library. The changing role of academic librarians as knowledge managers emphasises the need to constantly update or acquire new skills and knowledge to remain relevant to the today’s library environment. Academic libraries may need to restructure their functions, expand their roles and responsibilities to effectively contribute and meet the needs of a large and diverse university community.

This article aims to give an overview of knowledge management and its role in universities and academic libraries. The article will report on the case study results of the academic librarians of the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg Libraries and their current knowledge management practices.

2. Knowledge management: an overview

Knowledge management is a concept that has emerged explosively in the business community and has been the subject of much discussion over the past decade by various researchers and authors (Allee 1997; Bhatt 2002; Davenport & Prusak 1998; Probst, Raub & Romhardt 2000; Skyrme 1997; Wiig 2000). The essential part of knowledge management is, of course, knowledge. To determine what knowledge management is, it is helpful first to distinguish the differences between data, information and knowledge.

2.1 Various knowledge concepts: from data to knowledge

Many writers have addressed the distinctions among data, information and knowledge (Allee 1997; Barquin 2000; Beller 2001; Bellinger, Castro & Mills 1997). According to Suurla, Markkula and Mustajarvi (2002, p.35), “data refers to codes, signs and signals that do not necessarily have any significance as such”. It means that data are raw facts that have no context or meaning of their own. Organisations collect, summarise and analyse data to identify patterns and trends. Most of the data thus collected is associated with functional processes of the organisation. On the other hand, information as a concept takes up different meanings, depending on the context in which is discussed. Data becomes information when organised, patterned, grouped, and or categorised; thus increasing depth of meaning to the receiver (Boone 2001, p.3). Through learning and adoption, information can be changed into knowledge (Suurla, Markkula & Mustajarvi, 2002). It is evident from literature that knowledge is an intrinsically ambiguous term, and therefore, defining it precisely is difficult. It is because different disciplines use the term to denote different things. Despite the difficulties in defining knowledge, it is well agreed that, “knowledge is the expertise, experience and capability of staff, integrated with processes and corporate memory” Knowledge is always bound to persons and validated in the context of application. A well-known distinction in this respect is that between explicit and tacit knowledge, a distinction first elaborated by Michael Polanyi (Skyrme, 2002). Polanyi (1966) cited in uit Beijerse (1999, p.99) stated that “personal or tacit knowledge is extremely important for human cognition, because people acquire knowledge by the active creation and organisation of their own experience”.

This implies that most of the knowledge is tacit and becomes explicit when shared. Tacit knowledge is personal, context-specific (Allee, 1997) and therefore hard to formalise and communicate. It resides in the brains of the people. Explicit or “codified” knowledge, on the other hand, refers to knowledge that is transmittable in formal, systematic language (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995). In other words, explicit knowledge is expressed as information in various formats that include published materials and manuals of rules, routines and procedures.

Knowledge and management of knowledge appear to be regarded as increasingly important features for organisational survival (Martensson, 2000). knowledge is a fundamental factor, whose successful application helps organisations deliver creative products and services. different as compared to organisations existed in one or two decades ago in terms of their functions, structures and style of management. Yu (2002) pointed out that organisations put more emphasis on understanding, adapting and managing changes and competing on the basis of capturing and utilising knowledge to better serve their markets. The central argument around which knowledge management revolves is that people hold a wealth of knowledge and experience that represents a significant resource for an organisation. Most of this knowledge is represented in a wide variety of organisational processes, best practices and know-how (Gupta, Iyer & Aronson 2000). However, knowledge is diffused, and mostly unrecognised.

Today organisations are fundamentally It is important for organisations to determine who knows what in an organisation and how that knowledge can be shared throughout the organisation. For the purpose of this research, knowledge management is thus: the explicit and systematic management of vital knowledge and its associated processes of creating, gathering, organising, diffusion, use and exploitation. It requires turning personal knowledge into corporate knowledge that can be widely shared throughout an organisation and applied (Skyrme, 1997).

Formalising knowledge management activities in an organisation may help create consistency of methods and the transfer of best practices. Furthermore, knowledge should add value to the organisation as well as being an important dimension. However, most organisations operate in environments that they cannot control. It is because of the changes and challenges that organisations are faced with in the global knowledge economy. organisations could improve their performance in the global economy. The success of organisations is subject to both internal and external forces that they must operate in order to survive. Knowledge management is a viable means in which organisations could improve their performance in the global economy. The success of organisations is subject to both internal and external forces that they must operate in order to survive.

2.2 The changing role of universities

Knowledge management as it evolved in the business sector is slowly gaining acceptance in the academic sector. Oosterlink and Leuven (2002) pointed out that, “in our era of knowledge society and a knowledge economy, it is clear that universities have a major role to play”. In other words, universities are faced with a challenge to better create and disseminate knowledge to society. However, Reid (2000) argued “traditionally, universities have been the sites of knowledge production, storage, dissemination and authorisation”. Similarly, Ratcliffe-Martin, Coakes and Sugden (2000) articulated that universities traditionally focus on the acquisition of knowledge and learning.

As organisations (recognised to be in the knowledge business), universities and other higher education institutions face similar challenges that many other non-profit and for-profit organisations face (Rowley, 2000; Petrides & Nodine, 2003). Among these challenges are financial pressures, increasing public scrutiny and accountability, rapidly evolving technologies, changing staff roles, diverse staff and student demographics, competing values and a rapidly changing world (Naidoo, 2002). Universities seek to share information and knowledge among the academic community within the institution. Knowledge management has become a key issue in universities due to changes in knowledge cultures. Oosterlink and Leuven (2002)

argued that:

Universities are no longer living in splendid isolation.

They have their own place in society, and they have a

responsibility to society, which expects something in

return for privileges it has granted.

In other words, universities do not exist as single entities. They are part of society through engaging in teaching, research and community service. Therefore, the knowledge created in universities through research and teaching should be relevant to the labour market.

conservation of knowledge and ideas; teaching, research, publication, extension and services and interpretation (Budd, 1998; Ratcliffe-Martin, Coakes & Sugden, 2000). As a result, promoting knowledge as the business of the university should be the major focus of higher education institutions. It may be noted that the university is concerned with the Similar to corporate organisations there are forces that are driving the changes in the way universities operate. Nunan (1999) cited in Reid (2000) argued that “higher education is undergoing transformations due to a range of external forces such as market competition, virtualisation and internationalisation, giving rise to new ways of understanding the role and function of the university”. This implies that the present- day economic, social and technological context is bringing about changes to which universities must also adapt (CRUE, 2002). Universities compete against each other due to a great number of people who have access to higher education. Furthermore, the competitive pressures universities are now experiencing also result from changes in financial support, increasing costs of education and demand for educational services. Again, the present speed of knowledge transfer has generated an increasing demand from professionals and businesses for continuing education (CRUE, 2002).

This shift to a market orientation will alter the form in which knowledge is disseminated. That is, the focus of universities is moving away from the autonomy professionals and toward an integrated sharing of knowledge. Abell and Oxbrow (2001, p.230) pointed out that, “as with all organisations, academic institutions have recognised that their strength in the market may in future hinge on their ability to build collaborative and strategic partnerships”. These demands require the development of partnerships between universities and curricula customised to meet students’ needs. It can be noted that universities are complicated environments, incorporating a variety of very different kinds of work. As is true of all organisations, the universities have their own political structures and their own cultures (Budd, 1998, p.6). In addition to that, they have their own ways of responding to the society. Another challenge that universities face, is demographic changes and that affects the institution’s delivery of education and also the library’s delivery of service. It is a challenge that requires universities to restructure their services to meet the needs of the academic community.

It is suggested that institutions of higher education gear up for a massive increase in the demand for educational services (Stoffle, 1996). Hawkins (2000) highlighted that collaboration requires the actual commitment and investment of resources, based on a shared vision. As a result, universities may be required to pool their resources in terms of human expertise, skills and competencies to achieve their goals. These challenges which occur as a result of change and transformation demands that universities come to grips with the notion that collaboration is one of the means of competitive survival (Hawkins, 2000).

In addition, the universities’ market demands are changing in terms of improving student learning outcomes. Some of the changes taking place in higher education have a direct impact on the library and its services. These include alterations in institution’s curricula, demographic changes in student bodies and additions to the media used in the classroom and in support of research (Budd, 1998). This translates to a demand that cannot be met with current resources, present bureaucratic structures and traditional methods for delivering services. Reid (2000) pointed out that this causes universities to measure their teaching programmes, at least to some extent, as a market commodity that is aimed to meet the needs of the customer. In addition, universities will be required to re-examine all traditional methods and frameworks for a university education. In doing so, the discussion about this re-examination of the university will move into the same kind of paradigm shifting as that about libraries (Stoffle, 1996). It is also a challenge to academic libraries to support the needs of students for virtual learning.

libraries are turning to be “libraries without walls” and the information they deal with is now multi-format. Due to these challenges, it is clear that academic Furthermore, emerging information and communication technologies (ICTs) allow for the virtualisation of teaching and learning (Reid, 2000). universities makes it possible for courses, modules and training programmes that are interactive and multimedia based to be delivered on any time any place basis (Stoffle, The use of ICTs in 1996). This has created competition between universities in terms of delivering higher education services to the academic community. In addition, universities have been influenced by the modes of organising that dominated the corporate world and institutions. The upshot of the foregoing is that universities are facing the need for massive change in organisational structure, organisational culture in order to facilitate and integrate the sharing of knowledge within the university community. Commitment to change and learning together is important in that it combines to turn the universities into learning organisations.

2.3 Role of knowledge management in universities

As organisations grow ever complex, the organisational structures reflect specialisation in knowledge and expertise. Budd (1998) argued that higher education, as it grew, took an organisational characteristic of these other institutions, because there was increasing organisational complexity, that is, the level of knowledge and expertise in an organisation. As a result, today many educational institutions are seeking better ways to transform that knowledge into effective decision-making and action (Petrides & Nodine, 2003). The focus of universities, is based on making individual knowledge reusable for the achievement of the missions of the university.

However, Ratcliffe-Martin, Coakes and Sugden (2000) argued that:

Universities do not generally manage information well. They tend to lose

it, fail to exploit it, duplicate it, do not share it, do not always share it, do

not always know what they know and do not recognise knowledge as an

asset.

In order for universities to achieve their institutional mission, that is, education, research and service to society, they need to be consciously and explicitly managing the processes associated with the creation of knowledge. Academic institutions exist to create knowledge, and thus, they have a role to play. Knowledge management should have significance in higher education institutions. Sallis and Jones (2002, p.74) pointed out that education ought to find it easier to embrace knowledge management ideas, processes and techniques than many other organisations. Oosterlink and Leuven (2002) emphasised that with a suitable and multifaceted approach to knowledge management, universities can guarantee their own survival and at the same time prove that they are essential to modern society.

This is supported to some extent by Achava-Amrung (2001), who stated that

“knowledge management involves setting an environment that allows college and university constituencies to create, capture, share and leverage knowledge to improve their performance in fulfilling institutional missions”. Knowledge management is an appropriate discipline for enabling a smooth integration of these new needs that have arisen from the present economic, social and technological context, into higher education. management should aim at both internal reorganisation of resources and improving teaching and research (CRUE 2002). It is clear in the era of a knowledge society and a knowledge economy that universities have a major role to play. Stoffle (1996) pointed out that:

The application of knowledge

It is in this area that academic libraries have a unique

window of opportunity to help shape the future of both

the library and the institution and it is the library’s

educational and knowledge management roles that hold

the keys to success in this new arena.

Academic libraries have always facilitated information exchange, so they are well placed to take on knowledge management functions.

2.4 Academic libraries and knowledge management

As mentioned earlier, academic libraries face unprecedented challenges in the 21st century. Libraries are human organisations, so they are subject to the same sort of influences that many other organisations must deal with (Budd, 1998). The changing environment of academic life demands new competencies in academic librarians (Mahmood, 2003). As a result, the knowledge and expertise of academic librarians needs to be seen as the library’s greatest asset. The following section is divided into three main parts. The first part highlights a number of important issues facing academic libraries. The second part looks at how knowledge management practices could be applied in academic libraries. The final part explores the skills and competencies needed to carry out knowledge management activities within academic libraries.

2.4.1 Changing environment and issues facing academic libraries

2.4.1.1 Multiple formats of information

The rapid growth of information and communication technologies (ICTs) are said to be changing the way academic libraries operate today. Academic library collections are no longer collections comprised almost entirely of printed materials but collections comprised almost of materials in multiple formats and media (Budd, 1998). Information technologies such as computers, multimedia and CD-ROMs are bringing unprecedented abilities to academic libraries in providing services and resources to the university community. Over the past few years, the Web has had a tremendous effect on the growth of information and the speed of transmission. The problem with the Web is that, there is no real organisation of information like in the case of libraries. New means to deliver information over the Web places a challenge to academic librarians in terms of helping students make sense of information found on websites.

Another challenge facing academic libraries in the networked online environment is into exploit all forms of digital and telecommunication technologies and find new ways and means to provide feasible forms of collections; services and access to library materials (Foo et al., 2002). These technologies however, require greater responsibility to academic librarians. The challenge for academic librarians is to manage services, which offer users a carefully selected mix of multiple formats and media. Academic libraries should rethink their role in the whole university community. There is a need to support the needs of the users since the teaching and learning patterns in universities have changed. As information and research resources become more varied, this places a challenge to academic libraries. information, in research strategies and in the structure of higher education are affecting academic libraries. These changes define much of the shifting context within which academic libraries must operate. The changes brought by electronic Hazen (2000) argued that the changes in the nature of media necessitate transformation in the way librarians think about their jobs, the users of information and communication process of which they are part of (Budd 1998, p.270). Academic librarians must strive to remain competent navigators of each medium on order to assist the library users.

2.4.1.2 Changing user needs

As universities’ market demands are changing in terms of improving students learning outcomes, this has a direct impact on academic libraries and their delivery of services. Due to societal and technological developments, traditional teaching changes increasingly in creating learning environments.

learning processes via more ‘indirect’ contacts with teachers and facilities, including scientific information (Van Bentum & Braaksma, 1999). In addition, the teaching and learning patterns have developed towards greater modularisation and place an emphasis on self-directed, independent study and student-centred learning (Farley, Broady-Preston & Hayward 1998, p.154). This places greater demands on the library, which is increasingly being used for group work, and librarians face increased pressure on the enquiry service and a greater need for user support and education. Students participate in flexible Academic libraries have to provide information services for users acting in the changing academic environment. Academic librarians need to liaise with library users, faculties and schools to support the effective teaching, learning and research in universities. As Parker and Jackson (1998) explained, liaison is particularly important in a world of resource-based learning where students are encouraged to carry out more independent work and make wider use of a range of learning resources (including electronic information resources).

libraries to offer user-friendly ICT oriented facilities (like remote access to information and services), analyse the changing user needs and give support to users in new academic environments. The challenges require academic

2.4.1.3 Organisational structures

As a result of rapid environmental changes, academic libraries need to rethink their organisational structures in an attempt to provide quality service to the university community. The question to ask is: are academic libraries organisationally capable of addressing the challenges and issues facing them? Hazen (2000) pointed out that the structures that define academic libraries vary between countries, between institutions and between types of institutions. In other words, the type of organisational structure existing in academic libraries is determined by their readiness to deal with current challenges. Stoffle (1996) suggested that “we must flatten our organisations and eliminate the bureaucracies that make us inflexible and slow in our response to our environment and the opportunities that are constantly presented”. organisational structures are more conducive to innovation than are rigid hierarchies (Edwards & Walton, 1996). They promote the creation of ideas. Flatter There is a need to reshape the structure of academic libraries so that they will be able to improve the services they provide to both today’s and tomorrow’s users. Wilson (1998, p.17) urged university librarians to make their organisations more client- centred, to redesign work processes in light of organisational goals, and restructure in order to support front-line performance. The emphasis is more on the needs of the library user than the needs of the library. Moran (2001) argued that the hallmark of a learning organisation is information sharing, team-based structure, empowered employees, decentralised decision making and participative strategy. organisations, academic libraries need to reshape their structures to better serve their users.

2.4.1.4 Changing role of academic librarians

In an age of great change in information formats, delivery models and technologies, an important new role emerges for the academic librarian (CETUS, 1999). Bertnes (2000) argued that knowledge workers will be the most important profession in this century. There is no doubt that they are librarians. One of the major roles of academic librarians in the knowledge economy is that of knowledge managers. It is evident that academic librarians can no longer meet the information needs of the university community through the traditional avenue of simply adding to their library collections. Academic librarians need to go an extra mile. They need to understand the information and knowledge needs of users. They should be in a position to map internal and external knowledge that would assist them in increasing their efficiency. In other words, academic librarians should extend their information management roles and enhance their knowledge management competencies. Foo et al., (2002) pointed out that academic librarians as knowledge workers, need to play active roles in searching for innovative solutions to the issues involved in adapting to new environments.

2.5 Applying knowledge management practices in academic libraries

The basic goal of knowledge management within libraries is to leverage the available knowledge that may help academic librarians to carry out their tasks more efficiently and effectively. Knowledge management is also aimed at extending the role of librarians to manage all types of information and tacit knowledge for the benefit of the library. Knowledge management can help transform the library into a more efficient, knowledge sharing organization (Jantz, 2001, p.34). Kim (1999) pointed out that knowledge management practices aim to draw out the tacit knowledge people have, what they carry around with them, what they observe and learn from experience, rather than what is usually explicitly stated. It is important for academic libraries to determine and manage their knowledge assets to avoid duplication of efforts. Knowledge management process involves the creation, capturing, sharing and utilisation of knowledge.

2.5.1 Knowledge creation

Whether the key objective of academic libraries is to provide resources and information services to support the university community, the key resource that is required is knowledge. knowledge of library users and their needs, knowledge of the library collection and knowledge of library facilities and technologies available. These types of knowledge must be put together so that new knowledge is created which leads to the improvement and development of service to the users and functioning of the academic library.

However, this diverse knowledge is rather dispersed across all library sections and up the library hierarchy. The knowledge is not held by one individual only but by a number of individuals. Newell et al. (2002, p.48) pointed out that:

Knowledge creation is typically the outcome of an interactive process that

will involve a number of individuals who are brought together in a project

team or some other collaborative arrangement.

Only where there is interaction and communication can be a comparison of each person’s ideas and experiences with those of others. particularly important process of knowledge management. That is, the knowledge of the library’s operation, the Knowledge creation is a It focuses on the development of new skills, new products, better ideas and more efficient processes (Probst, Raub & Romhardt, 2000). In addition, knowledge creation refers to the ability to originate novel and useful ideas and solutions (Bhatt, 2001). As a result, when an organization knows what it knows, values and prioritizes that knowledge, and develops systems for leveraging and sharing, it leads directly to the creation of new knowledge (Huseman & Goodman 1999, p.216). Knowledge in the context of academic libraries can be created through understanding the user needs and requirements as well as understanding the university’s curricula. Tang (1998) pointed out that from the library’s perspective, knowledge creation implies participating more in user’s reading and studying by identifying information needs. In order to succeed, academic library services must link with the university’s academic programme or curricula. knowledge creation process through participating in the teaching and research activities of the university. Knowledge creation in this context should involve all the management effort through which the academic library consciously strives to acquire competencies that it does not have both internally and externally. Academic librarians can become part of the

2.5.2 Knowledge capturing and acquisition

Capturing and acquiring knowledge is crucial to the success and development of a knowledge-based organization. Organizations often suffer permanent loss of valuable experts through dismissals, redundancies, retirement and death (Probst, Raub & Romhardt 2000, p.226). The reason for this is that much knowledge is stored in the heads of the people and it is often lost if not captured elsewhere. The surest way to avoid collective loss of organizational memory is to identify the expertise and the skills of staff and capture it.

Academic libraries need to develop ways of capturing its internal knowledge, devise systems to identify people’s expertise and develop ways of sharing it. processes of capturing knowledge can include collating internal profiles of academic librarians and also standardizing routine information-update reports.

In addition, successful libraries are those that are user-centred and are able to respond to users’ needs. As users became more sophisticated, academic libraries need to develop innovative ways to respond – to add value to their services. Academic libraries need to be aware and to aim at capturing the knowledge that exists within them. The type of enquiries, for example, that are most commonly received at the reference desk should be captured and placed within easy reach to better serve users in the shortest time possible. It is important to create a folder of frequently asked questions to enable academic librarians to not only provide an in-depth customized reference service but also to become knowledgeable about handling different enquiries. Huseman and Goodman (1999, p.204) pointed out that there are times when an organization does not possess certain knowledge internally and does not have the skills to find it. As a result, academic libraries find themselves unable to develop the know-how that they need. Extra knowledge must therefore be acquired somehow if it is felt it will be useful to the goals of the academic library. The academic library as an organization may want to look outside its own boundaries to outsource or acquire new knowledge. From the point of view of knowledge management, outsourcing may be described as substituting external know-how for internal know-how (Probst, Raub & Romhardt, 2000).

In addition, as work practices change and people work more flexibly, it is important to provide ways to allow them to access external information (Westwood, 2001). Librarians have been dealing with building and searching online databases for a longtime. This kind of experience can be very helpful in building knowledge bases and repositories, a crucial area of knowledge management for managing organizational memory (Foo et al., 2002). Knowledge acquisition is the starting point of knowledge management in libraries (Shanhong, 2000). Knowledge in academic libraries can be acquired through:

• Establishing knowledge links or networking with other libraries and with institutions of all kinds;

• Attending training programmes, conferences, seminars and workshops;

• Subscribing to listservs and online or virtual communities of practice;

• Buying knowledge products or resources in the form of manuals, blueprints, reports and research reports.

Academic libraries need to gear up to equip academic librarians with the know-how they need to cope with the rapid changes of the 21st century, which is more information driven and knowledge-generated than any other area.

2.5.3 Knowledge sharing

Expertise exists in people, and much of this kind of knowledge is tacit rather than explicit (Branin, 2003), which makes it difficult to be shared. At its most basic, knowledge sharing is simply about transferring the dispersed know-how of organisational members more effectively. experiences gained internally and externally in the organization. Making this know- how available to other organisational members will eliminate or reduce duplication of efforts and form the basis for problem solving and decision-making. Knowledge sharing is based on the In the context of academic libraries, it can be noted that a great deal of knowledge sharing is entirely uncoordinated and any sharing of information and knowledge has been on an informal basis and usually based on conversation. Although knowledge has always been present in organizations, and to some extent shared, this has been very much on an ad hoc basis, until recently it was certainly not overtly managed or promoted as the key to organisational success (Webb, 1998). More emphasis is placed on formalizing knowledge sharing.

Jantz (2001, p.35) had pointed out that in many library settings, there is no systematic approach to organizing the knowledge of the enterprise, and making it available to other librarians and staff in order to improve the operation of the library. academic libraries to utilize their know-how, it is necessary that they become knowledge-based organizations. Academic libraries need to prepare themselves for using and sharing knowledge. To determine if there is any practice of knowledge sharing in academic libraries, we need to ask ourselves these questions: are academic librarians encouraged to share knowledge? Are the skills and competencies in the academic library identified and shared? How is the knowledge shared? Is knowledge sharing the norm? The expertise and know-how of organisational members should be valued and shared. Probst, Raub & Romhardt (2000, p.164) have pointed out that it is vital that knowledge should be shared and distributed within an organization, so that isolated information or experience can be used by the whole company. In reality, distribution and sharing knowledge is not easy task (Davenport, 1994). However, it is important for organizations to motivate why knowledge is being shared. The importance of knowledge sharing should be based on the capability of academic librarians to identify, integrate and acquire external knowledge. This should include knowledge denoting library practices, users and operational capabilities.

2.6 Skills and competencies needed for knowledge management

Knowledge management activities are aimed at facilitating the creation, capturing and acquisition, sharing and utilization of knowledge.such knowledge-enabling initiatives in the workplace requires the knowledge manager to apply several skills-sets (TFPL, 1999). In the perspective of academic libraries, there is a need for academic librarians to extend their expertise. transformation from librarian to knowledge manager is clearly underway (Church, 1998). However, this impending shift of incorporating knowledge management in the library activities requires a great deal of preparation. Bishop (2001) pointed out that the challenge for the information professional lies in applying competencies used in ‘managing information’ to the broader picture of ‘managing knowledge’. The greater challenge is managing the know-how of organisational members, which they acquire through years of experience.

The success of academic libraries depends on the capabilities and skills of its staff to serve the needs of the university community more efficiently and effectively. To be successful in this environment, individuals need to acquire new combination of skills (TFPL, 1999). Bishop (2001) argued that managing knowledge requires a mix of In making knowledge moretechnical, organisational and interpersonal skills. accessible, it useful to have knowledge of the organisation, customer service orientation and training skills (Koina, 2002). Teng and Hawamdeh (2002, p.195) summed up the skills needed by the information professional in a knowledge-based environment:

•IT literacy, that is knowing how to use the appropriate technology to capture, catalogue and disseminate information and knowledge to the target audience and knowing how to translate that knowledge into a central database for employees of the organisation to access;

• A sharp and analytical mind;

• Innovation and inquiring;

•Enables knowledge creation, flow and communication within the organisation and between staff and public.

It is important for academic libraries to encourage librarians to constantly update their skills and competencies in this changing environment.

3. Results and discussions

The following section will partly present and discuss the research results of a case study conducted at the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg Libraries. The research was aimed at understanding the knowledge situation of the library and to establish the ways in which the academic librarians could add value to their services by engaging with knowledge management.

3.1 Brief profile of respondents

The respondents work across various sections of the library with the major ones being the Issue Desk (34.8%), Subject Librarian Unit (26.1%) and Short Loan (21.7%). A large majority of the respondents were female (82.61%) and this is an indication that women largely dominate the profession. Almost half (52.17%) of the respondents were between 26 and 35 years old with the remaining ones almost evenly split between the ages 36-45 years (26.09%), 46-55 years (17.39%) and the smallest age group were over 55 years (4.35%). The results further indicated that a large majority of respondents have 6-10 years of working experience in academic libraries.

In terms of educational background, most of the respondents have a postgraduate degree in library and information science (see Figure One) and this show the demands of the profession in terms of keeping skills current. In addition to the qualifications, some of the academic librarians interviewed indicated that they keep updating their skills especially when new multimedia products are installed in the library.

3.2 Knowledge management practices

Respondents were asked to indicate the library’s use of formal, informal and everyday knowledge management practices in terms of current use and not in use. Knowledge management practices aim to draw out the tacit knowledge people have, what they carry around with them, what they observe and learn from experience, rather than what is usually explicitly stated (Kim 1999). Knowledge management practices were categorised into policies and strategies, leadership, knowledge capturing and acquisition and knowledge sharing.

3.2.1 Most knowledge management practices in use

3.2.1.1 Partnerships with other libraries

The study was interested to find out if the library does collaborate with other libraries. Overall, 73.9% respondents said the library had used partnerships with other libraries to acquire knowledge. Leveraging and sharing knowledge is a key component of partnerships or collaborations. Today libraries face innumerable challenges that are so complex and interrelated that no single librarian, library manager or library can cope to address them alone. In order to address these challenges, libraries need a broad array of knowledge, skills and resources. become increasingly networked, libraries have begun to form new partnerships with other libraries to develop and improve services and products that support users and advance access to scholarly information. Cohen and Levinthal (2000:39) pointed out that “the ability of a firm to recognise the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it, to commercial ends is critical to its innovative capabilities”. The same applies to academic libraries, in that librarians need information and knowledge to effectively improve their services for users in an increasingly complex and sophisticated information environment. As the information environment has

3.2.1.2 Knowledge sharing

The study also wanted to find out if staff was systematically sharing their know-how, expertise and experiences through various mechanisms. Respondents indicated that they shared knowledge informally within the library (87.0%), preparing written documentation such as newsletters (82.6%), and in collaborative work by teams (52.2%). The study also wanted to find out the level of knowledge sharing in the library. Overall, 47.8% of the participants said that knowledge sharing in the library was on average, 21.7% mentioned that it was good, 17.4% said it was poor and 13.0% indicated that it was unsatisfactory. It can be argued that though the library does share knowledge to some extent, however, there is little systematic sharing of knowledge taking place among the academic library staff. More emphasis should be placed on formalising knowledge sharing activities.

3.2.2 Knowledge management practices not in use

3.2.2.1 Policies and strategies

Respondents (60.9%) indicated that the library had no written knowledge management policy and strategy and 39.1% respondents said they were not aware of any knowledge management policies or strategies in place. The results indicate that knowledge management is not seen as an integral part of the library’s mission and objectives. In addition, the results indicate that there is a lack of awareness of knowledge management in the library. In most cases academic libraries do not systematically or formally harness and manage their knowledge management activities.

3.2.2.2 Leadership

With regard to who takes part in leading knowledge management activities, the results indicate neither the University Librarian (78.3%) nor the library staff (56.5%) is involved in knowledge management activities. With the follow-up interviews conducted, the library staff indicated that if the library has to implement knowledge management, they need the support of management and that the University Librarian should play a leadership role in knowledge management activities.

3.2.2.2 Knowledge capturing and acquisition

The study was interested to find out if the library had captured and acquired the knowledge of its internal staff. Overall, 87.0% of respondents indicated that there was no capturing and acquisition of knowledge of internal staff. The results show that the library has not recognised the capacity of its staff. Capturing and acquiring knowledge is crucial to the success and development of a knowledge-based organisation. With the follow up interviews conducted, participants indicated that there was a high staff turnover. The participants mentioned that the know-how and expertise of the retired and resigned staff has not been captured elsewhere. As Probst, Raub and Romhardt (2000:226) had said “organisations often suffer permanent loss of valuable knowledge through dismissals, redundancies, retirement and death”. It is important for the library to gear towards developing ways to capture the expertise and know-how of its staff.

3.3 Possible reasons to apply knowledge management practices

This question was trying to find out the possible reasons to apply knowledge management practices in the library. Respondents (69.6%) found that promoting the sharing or transferring of knowledge with users such as lecturers and students was critical. It is because the role of academic libraries is to provide and disseminate information to its users.

important to identify and protect strategic knowledge present in the library. Lee (2000) pointed out that the knowledge and experiences of library staff are the intellectual assets of any library and should be valued and shared. The success of academic libraries depends on their ability to utilise information and knowledge within.

3.4 Skills needed for knowledge management

The study was trying to find out the skills that academic librarians need in order to better serve the needs of the users. The results show that academic librarians are in need of skills and competencies that could help them engage in knowledge management activities. It is indicated in the literature that the success of academic libraries depends on the capabilities and skills of its staff to better serve the needs of the university community more efficiently and effectively. Academic librarians need to constantly update their skills and competencies.

3.5 Motivation to implement knowledge management practices

The study wanted to find out what could motivate the library to implement knowledge management practices. Participants indicated the following:

• The difficulty in capturing staff’s undocumented knowledge;

• Loss of key personnel and their knowledge;

• To contribute to knowledge creation of knowledge to the parent university;

• To increase knowledge sharing and

• To increase staff productivity.

It can be noted that there are various reasons into which organisations embark on knowledge management activities.In the case of the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg Libraries the problem lies with lack of capturing the knowledge of staff. Knowledge capturing is an important process that enables individual knowledge to be reusable in the whole organisation. The library should establish ways in which knowledge could be captured.

source : citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.137.8283

Hal yang dapat di pelajari dari kasus di atas adalah bahwa universitas natal ini berusaha untuk meningkatkan pelayanan mereka dalam sharing informasi dengan menerapkan Knowledge Management. agar knowledge Management ini dapat berjalan maka para karyawannya di harapkan mampu untuk menerapkan budaya sharing informasi berbagi pengetahuan . selain itu , keberhasilannya juga tergantung pada kemampuan para karyawannya dalam memanfaatkan informasi dan pengetahuan. pengetahuan dan pengalaman merupakan aset intelektual suatu perpustakaan , apabila ke duanya tidak di jalankan maka akan menimbulkan suatu masalah.

Under Terra’s Optics

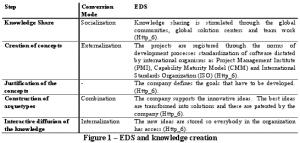

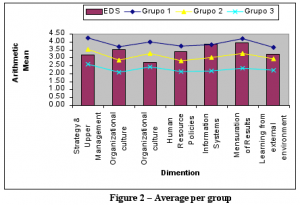

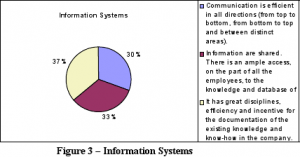

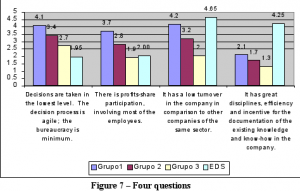

Under Terra’s Optics Through figure 2, it is possible to conclude that EDS presents a bigger degree of agreement with group 2 – traditional companies. However, it is important to highlight that the topics Information System and Mensuration of Results are part of group 1. But, in the other hand, Structure Organizational is part of group 3. Three questions were answered in the System of Information topic. Analyzing them through figure 3 we can observe that all questions had practically the same weight on the average.

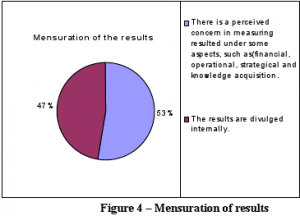

Through figure 2, it is possible to conclude that EDS presents a bigger degree of agreement with group 2 – traditional companies. However, it is important to highlight that the topics Information System and Mensuration of Results are part of group 1. But, in the other hand, Structure Organizational is part of group 3. Three questions were answered in the System of Information topic. Analyzing them through figure 3 we can observe that all questions had practically the same weight on the average. The company has a perceived concern in evaluating the projects, looking to identify the sources of acquisition, generation and diffusion of the knowledge that they are excellent. The result of this constant work is showed in figure 4.

The company has a perceived concern in evaluating the projects, looking to identify the sources of acquisition, generation and diffusion of the knowledge that they are excellent. The result of this constant work is showed in figure 4. The worst evaluation occurred in the question related to the organizational structure, which can be compared with the group of small companies, who are less associated with effective management of knowledge. In figure 5, the only question that possesses weight bigger than the average is the one related to small reorganizations.

The worst evaluation occurred in the question related to the organizational structure, which can be compared with the group of small companies, who are less associated with effective management of knowledge. In figure 5, the only question that possesses weight bigger than the average is the one related to small reorganizations. The questionnaire was composed of 41 questions, all of them related to the seven dimensions. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the averages per question with the results obtained for Terra (Terra, 2000). Through this figure, it can be observed that two average questions with very low average rates and two high average rates in comparison with groups 1, 2 and 3.

The questionnaire was composed of 41 questions, all of them related to the seven dimensions. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the averages per question with the results obtained for Terra (Terra, 2000). Through this figure, it can be observed that two average questions with very low average rates and two high average rates in comparison with groups 1, 2 and 3. The two questions that presented the smallest degree of agreement between the respondents are:

The two questions that presented the smallest degree of agreement between the respondents are: Suggestions

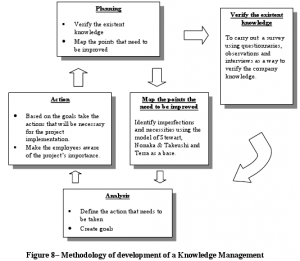

Suggestions This methodology presents three stages: planning, analysis and action. In the stage of planning the verification of the existing knowledge in the organization is executed, using the models of Nonaka and Takeuchi (Nonaka, 1995), Stewart (Stewart, 1998) and Terra (Terra, 2000). It also executes the mapping of the existing knowledge to identify the imperfections and necessities based on the models. The stage of analysis includes the definition of the actions to be taken and creation of goals for the project. The last stage, which is the action, consists of taking action and making the employees aware of the importance of the project.

This methodology presents three stages: planning, analysis and action. In the stage of planning the verification of the existing knowledge in the organization is executed, using the models of Nonaka and Takeuchi (Nonaka, 1995), Stewart (Stewart, 1998) and Terra (Terra, 2000). It also executes the mapping of the existing knowledge to identify the imperfections and necessities based on the models. The stage of analysis includes the definition of the actions to be taken and creation of goals for the project. The last stage, which is the action, consists of taking action and making the employees aware of the importance of the project.