Knowledge Management and Dublin Core

1. Introduction

The application of Dublin Core (DC) metadata for information management purposes has been taking place ever since the 15 simple DC elements were developed. Its application for industry specific purposes such as education or government service identification has also been widely adopted, though not without challenges along the way.

Knowledge Management (KM) presents an interesting set of challenges for those interested in utilising DC metadata because it can be perceived as a number of different things – as an academic discourse, an organisational intervention, a set of activities that a community of practice might undertake to ensure optimum knowledge flows, or even what an individual might do to maximize the reuse and retrievability of their own knowledge. To underscore this challenge, it is a very interesting exercise just to find a broadly accepted definition of KM that might be both flexible and comprehensive enough to deal with all these scenarios.

Although KM first emerged in the 1980s it only began to seriously establish in the mid 1990s when the impact of the Web was just beginning to be felt upon the business world. As such, its early character was biased toward business process improvement from a managerial perspective.

The influence of networks upon the way KM has been understood or implemented is something that has only emerged in later discourse (Beerli, et al., 2003; Back, et al., 2006). It has been argued that the fundamental KM problem is all about changing organizational ‘silos’ of activity (manifest in organizational divisions, hierarchical management structures, projects, work teams, documents, and individual workspaces) so that knowledge flows more readily, is shared and leveraged for maximum benefit, and is not pigeonholed nor rendered inaccessible through poor information management practices (Xu and Quaddus, 2005: 382).

Such a problem will likely resonate for most people who are employed by organizations. However, while this ‘silo’ problem is clearly evident within hierarchically structured organizations it is also manifest within networks, and it is commonplace for potentially synergistic communities of practice to actually exist more as disconnected ‘islands’. The problem is in fact a deeper one, and is to do with the nature of knowledge and organization—hierarchies and networks are the two most effective forms of organisation that human beings have yet created; both have their place, but it will always be the situational context that will suggest the most effective way to act.

Another challenge concerning KM for the DCMI community is that it represents a domain that is arguably more expansive than all other communities currently developing application profiles. Thus, a definition of Knowledge Management that might be useful for the DCMI KM community to consider is presented here:

Knowledge Management (KM) finds expression as both an organisational intervention aimed at delivering better efficiencies in the handling of knowledge, and an academic discourse that develops theoretical frameworks and practical techniques for managing the entire knowledge lifecycle from a variety of perspectives: individual, community, and organisational. It can, though doesn’t need to, involve a multiplicity of considerations and tasks and is always influenced by context.

1.1. DCMI KM Community

The DCMI Knowledge Management Community was established in mid 2007 as “a forum for individuals and organisations with an interest in the application and use of the Dublin Core standard in knowledge management.” (DCMI, 2007) To some extent this new community provides continuity with issues addressed by the DCMI Global Corporate Circle, which was deactivated in 2007. To date, while there is clearly an interest in this area with over 120 subscribers to the email listserv there is little serious documented discourse. This paper therefore aims to make a contribution by presenting some theoretical framework for consideration, providing examples of how DC metadata is being effectively applied in some Knowledge Management (KM) contexts, and pointing to current limitations of DC in such contexts.

1.2. Overview

The following discussion deals with topics on modelling and organising knowledge from a theoretical perspective. A number of scenarios are then presented, indicating how DC metadata has been effectively utilised for KM purposes. A sense-making abstraction is presented as a reference model for identifying prominent facets or pathways of knowledge that will typically need to be considered in KM contexts. This model aims to validate current applications while also pointing to potential novel applications, thereby indicating any limitations with currently available schemas that may need to be overcome.

2. Representing, Modelling, and Managing Knowledge

For knowledge to be organised and managed it is necessary to first establish the scope of such an undertaking. This task has been approached by various practitioners and communities of practice in a broad variety of ways. The proceeding discussion is an attempt to summarise some of the more prominent approaches that have relevance for the application of DC metadata.

The field of Computer Science provides at least two key (mutually informing) approaches – through formal knowledge representation languages such as Prolog, the Resource Description Framework (RDF), the Web Ontology Language (OWL), and Attempto Controlled English (ACE); or, through conceptual classification into three categories: declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge. Declarative knowledge is expressed by explicit statements of the kind ‘it is known that’ and typically involves facts or ‘objective’ information; procedural knowledge is typically expressed by statements that represent ‘know-how’; and, conditional knowledge is represented by statements that represent ‘knowing-if’ and/or ‘knowing-why’ (Murphy, 2008).

Through recent years of work on developing a robust ‘abstract model’ that can inform future extensibility and application of DC metadata, the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative is now strongly aligned with the knowledge representation capabilities of RDF (Powell, et al., 2007). It is noteworthy that this work has taken both considerable effort and time and has required ongoing explication through other documents such as the Singapore Framework (Nilsson, et al., 2008). This work has also demonstrated that the goal of defining and using shared semantics is not sufficient for sustainable knowledge sharing in Web environments—for this to occur, semantics must be associated with statements that make clear certain relationships, thereby establishing context through syntax and structural relations. Another approach is to situate knowledge within its relationship to data, information, and wisdom as a value hierarchy and is often depicted as a pyramid .

However, just as the Internet has rendered geographical boundaries and legal jurisdictions as debatable constructs when it comes to information flows, the boundaries that separate data, information, and knowledge can be very fuzzy and depend upon context. Thus, in the context of the Internet, Figure 1 becomes a very poor representation for the simple reason that data, information, and knowledge become intermeshed. In this environment value can be created through rendering information and knowledge as data and many datasets can either comprise or be extracted from a knowledge-base. In short, this inverts the value-chain depicted by the pyramid (Mason, et al., 2003). Capturing explicit knowledge and organising it as structured information for sharing and reuse is thus one of the powerful features and potentials of the Web. This same recursive property can also be seen with metadata. While it is pragmatic that simple models identify ‘digital assets’ or content as one entity and ‘metadata’ as another (that describes the content) such models can mask deeper complexity. For example, in the case of a repository designed to broker resource discovery, the assets it gathers into a collection might only be metadata records but collectively they represent useful content – thus, ‘one person’s metadata may be another’s content’; ultimately, it is the context that determines this (Mason, 2004).

But there is another reason why Figure 1 is not adequate for the Internet and that has to do with the important role that metadata has in the organisation, structuring, presentation, and sharing of content and services—metadata being defined as data associated with or descriptive of other data, information, knowledge, or services. As such, metadata can be expressed in many forms— examples include the manifest file associated with a ‘learning object’, XML tags, user-defined tags, or explicit information such as authorship or publication date of a piece of content. A more accurate representation would therefore be something like what is depicted in Figure 2.

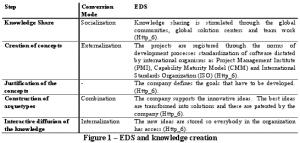

Yet another approach, from the field of Knowledge Management, was inspired by Polanyi (1966), who distinguished between explicit and tacit knowledge. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) developed this concept further and proposed a dynamic model that represents the management of (organisational) knowledge as interactions of tacit and explicit knowledge throughout four on going processes involving socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization known as the “SECI model”. As both an academic discipline and an organisational intervention the field of KM has developed considerably in the past decade and is replete with many more detailed models that both draw upon and challenge this foundational work (Snowden, 2002; Earl, 2001; Firestone and McElroy, 2002; Rao, 2005; Wierzbicki, 2006). Thus, while the core concepts of the SECI model continue to be recognised as important by KM practitioners the world over, there is an underlying shift in paradigm from a principle of reduction toward a principle of emergence that is important to highlight (Wierzbicki, 2006:1-13). The work by Snowden (2002, 2005) on complexity, story-telling, and sense-making is representative of this shift. Likewise, Seufert, Back, and von Krogh underscore the importance of networks for KM to develop:

Concerning the integration of networking and knowledge management, we believe two aspects to be crucial. First, knowledge management should comprise a holistic view of knowledge, meaning the integration of explicit and tacit knowledge. Furthermore, knowledge management should take a holistic view on where and how knowledge is being created and transferred … The integration of networking into knowledge management yields great benefits. The openness and richness of networks … foster a fertile environment for the creation of entirely new knowledge.

The influence of networks and networking upon KM suggests then that there is scope for developing updated models of knowledge. This is particularly so, given that hierarchies have historically been the dominant mode of organisational structure; however, while harnessing the flows of knowledge shared within networks would appear to be a natural domain for KM the theory and practice of doing so is not so straightforward. This is borne out in a blog post by Sims (2008) in which an analysis of 53 Knowledge Management definitions is presented:

General observation: this again illustrates the definition diversity. It is not like these are 53 definitions with slightly different word choice. These are substantially different. There are only five attributes that are seen in 30% or more of the definitions: KM is a process, it is targeted at the organization (company), it deals with knowledge, sharing is part of the story, and the definition includes a “why”. (Sims, 2008) Thus, it can be seen that the discourse on KM has developed considerably in the past 15 years. In an attempt at summing up the dimensions of ‘emergence’ and ‘complexity’ while not trivializing them Snowden advocates a characterization of the “paradoxical” nature of knowledge “as both a thing and a flow” (Snowden, 2002). As such, an adequate model of knowledge needs to convey dynamism and the tasks associated with organising knowledge involve far more than the description and classification of information resources—it involves both the tacit and explicit dimensions of knowledge. Obviously, metadata can only successfully be applied to explicit knowledge—so, is there another approach that can approximate a holistic view of managing knowledge? Could such a model point to new applications for metadata?

2.1. A Faceted Model

While all the preceding approaches can be shown to be useful a faceted model is presented as a means of identifying the critical pathways of knowledge in KM contexts (see Figure 3). This model is based upon earlier work in Norris, et al., (2003) and further refined in Mason (2007). This model represents an attempt to summarise the key pathways for consideration while an individual is engaged in learning, thinking, or knowing. It has been developed as a device that might assist in providing a ‘shorthand’ reference of considerations when approaching the development of an e-learning activity or a KM task. The model represents ‘primitive’ questions associated with query generation or proposition development (Who, What, When, Where, How, Why, and If). These seven knowledge facets are situated within three key influences: content, community, and context following Seely Brown (1999. p. ix).

Out of these seven primitives Who, What, When, and Where can be seen to function primarily as the primitives of organised information retrieval and resource discovery – particularly within the Internet. This can easily be validated by investigating the essential characteristics of metadata schemas used to describe information resources such as proposed by the DCMI Kernel Community (Kunze, 2001; Mason and Galatis, 2007). It is not yet clear to what extent the Why, How, and If primitives function as catalysts in the development of understanding but they can be seen as important questions in many activities that involve the creation, sharing, and management of knowledge. Of the latter three primitives, How and If can be seen to typically generate procedural or rule-based knowledge. Why, however, presents a significant challenge to deeper modelling, primarily because of its breadth of usage. Unlike the descriptive primitives (Who, What, When, Where, and to some extent, How), Why gives emphasis to the explanative dimension in which facts can be subject to greater subjective perspective. In teaching contexts Why is used as a question to help learners adopt a critical, reflective approach to the content they must interact with. In KM contexts, understanding why a certain communication protocol is important or why certain procedures need to be followed can make all the difference to how these things are operationalised. Knowing-why can also help build “strategic insight” (USDA FS, 2005:6).

There are a number of assumptions that underpin this model, not least of which is the choice of utilising a circular graphic—the assumption being that the relationships between all entities within it are closely interdependent. It is therefore instructive to consider recent literature focused on identifying transitions in knowledge creation that most models are presented as spirals (Wierzbicki and Nakamori, 2006). It is therefore acknowledged that this model could be improved and may need to be tested rigorously and modified.

3. Organising Information

Information can be organised in a multiplicity of ways—in library and enterprise settings the default method is through the application of hierarchical structure, based upon authoritative classifications and taxonomies (such as the Library of Congress Subject Headings or Dewey Decimal Codes); in Web environments, the power of association through hyperlinks is exploited; and, in a seemingly chaotic pile of papers on an office desk. In each case, structure and relation combine as the key organising principles. Focusing on semantics, as the DCMI community and Semantic Web community have done since first being established, also represents a powerful way to organise and discover information.

The simple (but extensible) semantics of the Dublin Core represent an elegant simplification of traditional library cataloguing semantics for use in Web environments. Following this achievement, it is arguable that the even simpler semantics proposed by the DCMI Kernel Community represent an important future key to innovative approaches to metadata interoperability (Kunze, 2001). The application of DC metadata to describe and enrich information resources has proven to be an effective method of managing information for later retrieval and reuse. In fact, metadata can be seen as a key component in managing information resources, But the question arises: to what extent can it be used in organising knowledge?

4. Organising Knowledge

For as long as knowledge has been preserved it has also been organized—whether in the context of non-literate societies such as Indigenous Australians stewarding knowledge through story and song; in the context of the I Ching, the first Chinese book ever written and focused on 64 core life scenarios to navigate; or, in the classification of newly identified plant species according to authoritative taxonomies.

Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) can be seen as a key contemporary technology that enables knowledge to be organised through rich associative links. Through combining hypertext with Internet transmission protocols HTML has enabled the Web to become a vast networking platform for connecting information and communication resources. While human societies have always benefited from networking, the scale and reach of networks now available is fundamentally a new development in human history and in the organisation of its disparate knowledge sources. Of course, most of the developed world now takes all this for granted. With recent developments in Semantic Web technologies and Web 2.0 applications there now exists further capacity for organising and sharing knowledge; however, the flipside of this story is that innovation is so extensive there is also a chaotic dimension to the proliferation of knowledge and networks. As soon as a new way of organising or combining knowledge becomes available new ‘islands’ or ‘silos’ of activity emerge and ‘networks’ soon become ‘clubs’ or ‘tribes’ that rely on conventions and protocols to participate.

‘Emergence’ is a concept that describes a scientific paradigm for our times in more meaningful ways than a scientific reductionist paradigm does (Wierzbicki and Nakamori, 2006)—but dealing with the pragmatics of this can be challenging to say the least! It is therefore arguable that in the same way that Jean-Paul Sartre made the famous comment that “man is condemned to be free” that no matter what knowledge we create we are condemned to make new sense of it in new contexts (Sartre, 1966). Just because knowledge may reside within an ‘open architecture’ platform doesn’t render it as operational, and it certainly doesn’t guarantee that it will flow. Because of the many methods of assigning order to otherwise unstructured information the Knowledge Organization System (KOS) is used to describe such methods. Examples include classification schemes, thesauri, taxonomies, controlled vocabularies, and subject headings. This term has been used as the basis for a relatively new Web technology, known as the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), which is aimed at providing a common data model for

the exchange of data between the kind of KOS referred to above (Miles and Bechhofer, 2008).

All these developments in technologies underscore that the application of metadata in any KM context represents just one component of a broader concern. In other words, metadata alone does not provide a complete solution for KM. Moreover, despite the use of the word ‘knowledge’ in technologies such as SKOS, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that such systems only represent a subset of knowledge. Furthermore, as Ray argues, Data models are insufficient to enable widespread system interoperability, and organizations need to develop an ontology to explain how different data elements interact. Only when this context is rendered in a computational form can external systems make sense of a data model. (Ray, 2009 quoted by Jackson, 2009).

4.1. Other Requirements

Because Knowledge Management is concerned with maximizing the potential application for both tacit and explicit knowledge, certain practical limits govern the application of DC metadata. In some KM contexts the ‘reusability’ of information or knowledge may be limited to basic metadata; however, in some corporate settings other metrics will apply. For example, the ‘trustworthiness’ or ‘reliability’ of the content or its source may depend on local or tacit knowledge about its origins; quality assessment will have industry-specific conventions; the ability to integrate diverse vocabularies in supporting IT infrastructure; the degree to which performance-support can be provided; how to prepare knowledge for transfer to contexts as yet not identified; what business analytics can be discerned; and, then there are security and privacy concerns. All these are issues for KM.

Many KM practitioners also place emphasis upon story as a means to communicate important lessons from the field. In terms of the model discussed in Figure 3, aspects of story align well with the facet know-why. The challenge becomes: how to use a DC approach in developing an appropriate schema to capture this?

5. Practical Perspectives

The following cameos are presented to indicate the diversity of implementation contexts in which Dublin Core metadata is currently used for KM purposes.

5.1. Ohio State University Knowledge Bank

The Ohio State University Knowledge Bank (OSUKB) represents an exemplar in University institutional repositories in the way it integrates diverse digital assets, is well-positioned to interoperate (or federate) with other ‘open access’ repositories, and the project “places its institutional repository in the larger context of a multifaceted knowledge management program” (Branin, 2004). The OSUKB also represents an example of the evolutionary path that academic libraries have navigated in recent years from “collection development to collection management to knowledge management” (Branin et al., 2007). Apart from the value of knowledge sharing with peers, the core value proposition presented to students in order to enlist their participation in using the Knowledge Bank is as a safe, high quality, managed repository in which to store and preserve outputs of their work for later use and or discoverability by others (OSU, 2009). This is clearly an important component of an individual student’s KM requirements. It also serves the purposes of the institution in that it represents an aggregation of intellectual outputs that will expand over time.

The OSUKB is an implementation of DSpace software and its Metadata Application Profile is based upon qualified Dublin Core (OSU, 2008). Specific additional requirements, such as managing Intellectual Property Rights, are handled via Creative Commons licensing. The OSUKB approach to KM represents a typical repository approach found throughout higher education settings worldwide. As such, the KM infrastructure that is implemented places emphasis on the management of scholarly outputs or content as the primary object for knowledge management. Despite acknowledging the broader KM agenda beyond the storage and retrieval of content to involve the “social life of information,” it is clear that there is a long way to go for other aspects of KM to be implemented as services that enhance the OSUKB—if Figure 3 is considered.

5.2. The Corporate Sector

While there is plenty of evidence that the corporate sector uses metadata to manage its assets, there still seems to be selective adoption of DC metadata. In fact, a recent book published with the title ‘Business Metadata’ (Inmon, et al., 2008), does not even contain one passing reference to DC metadata! This underscores the findings in a 2005 report developed for the DCMI Corporate Circle:

Except where there is a business or regulatory requirement to share information, the private sector has little interest in interoperability with repositories outside their organisation. Most applications that seek to gather metadata into databases so that document-like content can be found and re-used when needed, occur behind the firewall.

… [while there is] wide usage of Dublin Core in this context … there is an unwillingness and inability to share the details of that experience widely. (Busch, et al., 2005) This suggests that while some metadata infrastructure is being put in place to accommodate internal organisational information management requirements there is a long way to go before a holistic approach to KM metadata requirements in the corporate sector is achieved.

5.3. Semantic Web

With the development of the DCMI Abstract Model there is now exists better theoretical alignment with capabilities of RDF and hence the Semantic Web. The implications for KM of this are neatly summed up by Lamont (2007):

The Semantic Web is relevant to knowledge management because it has the potential to dramatically accelerate the speed with which information can be synthesized, by automating its aggregation and analysis. Information on the Web now is typically presented in HTML format, and while very beneficial in some respects, the format offers neither structure nor metadata that is useful for effective management. Cho (2009) echoes this view by arguing the role that Dublin Core has played in “knowledge management activity representation” is a key factor to future success of the Semantic Web. However, identifying significant Semantic Web implementations in KM contexts has not as yet been fruitful.

source : www.dublincore.org/groups/km/

Hal yang dapat di pelajari dari kasus diatas adalah bahwa penerapan knowledge management dalam dublin core metadata dapat memperbaiki proses bisnis dan perspektif manajerial dalam perusahaan diatas . selain itu , Knowledge Management (KM) juga menyajikan serangkaian tantangan yang menarik bagi mereka yang tertarik dalam memanfaatkan metadata DC karena dapat dianggap sebagai beberapa hal yang berbeda – sebagai wacana akademik, intervensi organisasi, satu set aktivitas bahwa komunitas praktek mungkin melakukan untuk memastikan arus pengetahuan yang optimal, atau bahkan apa yang individu mungkin lakukan untuk memaksimalkan penggunaan kembali dan retrievability pengetahuan mereka sendiri. serta KM dapat domain yang memiliki lingkup yang lebih luas dari masyarakat lain yang sedang mengembangkan profil aplikasi untuk metadata DC dalam rangka mengakomodasi metadata eksplanatif.

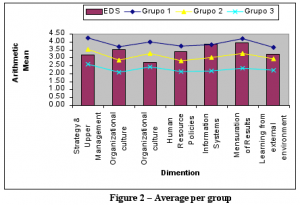

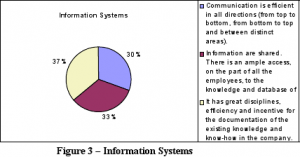

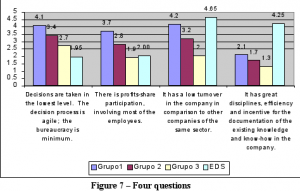

Through figure 2, it is possible to conclude that EDS presents a bigger degree of agreement with group 2 – traditional companies. However, it is important to highlight that the topics Information System and Mensuration of Results are part of group 1. But, in the other hand, Structure Organizational is part of group 3. Three questions were answered in the System of Information topic. Analyzing them through figure 3 we can observe that all questions had practically the same weight on the average.

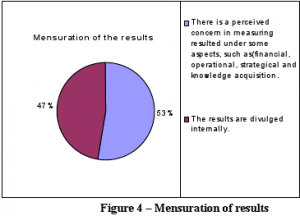

Through figure 2, it is possible to conclude that EDS presents a bigger degree of agreement with group 2 – traditional companies. However, it is important to highlight that the topics Information System and Mensuration of Results are part of group 1. But, in the other hand, Structure Organizational is part of group 3. Three questions were answered in the System of Information topic. Analyzing them through figure 3 we can observe that all questions had practically the same weight on the average. The company has a perceived concern in evaluating the projects, looking to identify the sources of acquisition, generation and diffusion of the knowledge that they are excellent. The result of this constant work is showed in figure 4.

The company has a perceived concern in evaluating the projects, looking to identify the sources of acquisition, generation and diffusion of the knowledge that they are excellent. The result of this constant work is showed in figure 4. The worst evaluation occurred in the question related to the organizational structure, which can be compared with the group of small companies, who are less associated with effective management of knowledge. In figure 5, the only question that possesses weight bigger than the average is the one related to small reorganizations.

The worst evaluation occurred in the question related to the organizational structure, which can be compared with the group of small companies, who are less associated with effective management of knowledge. In figure 5, the only question that possesses weight bigger than the average is the one related to small reorganizations. The questionnaire was composed of 41 questions, all of them related to the seven dimensions. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the averages per question with the results obtained for Terra (Terra, 2000). Through this figure, it can be observed that two average questions with very low average rates and two high average rates in comparison with groups 1, 2 and 3.

The questionnaire was composed of 41 questions, all of them related to the seven dimensions. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the averages per question with the results obtained for Terra (Terra, 2000). Through this figure, it can be observed that two average questions with very low average rates and two high average rates in comparison with groups 1, 2 and 3. The two questions that presented the smallest degree of agreement between the respondents are:

The two questions that presented the smallest degree of agreement between the respondents are:

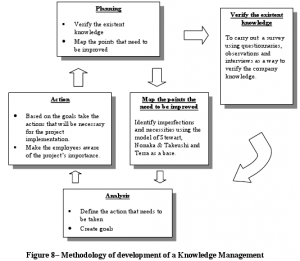

This methodology presents three stages: planning, analysis and action. In the stage of planning the verification of the existing knowledge in the organization is executed, using the models of Nonaka and Takeuchi (Nonaka, 1995), Stewart (Stewart, 1998) and Terra (Terra, 2000). It also executes the mapping of the existing knowledge to identify the imperfections and necessities based on the models. The stage of analysis includes the definition of the actions to be taken and creation of goals for the project. The last stage, which is the action, consists of taking action and making the employees aware of the importance of the project.

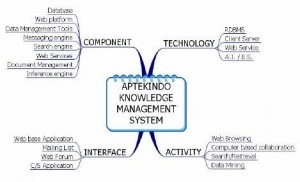

This methodology presents three stages: planning, analysis and action. In the stage of planning the verification of the existing knowledge in the organization is executed, using the models of Nonaka and Takeuchi (Nonaka, 1995), Stewart (Stewart, 1998) and Terra (Terra, 2000). It also executes the mapping of the existing knowledge to identify the imperfections and necessities based on the models. The stage of analysis includes the definition of the actions to be taken and creation of goals for the project. The last stage, which is the action, consists of taking action and making the employees aware of the importance of the project. Gambar 3 menunjukkan usulan gambaran umum konsep APTEKINDO knowledge management system. Sistem terbangun atas 4 pilar utama, yaitu teknologi, aktifitas, interface, dan berbagai komponen. Aktifitas yang diperlukan dalam sistem ini di antaranya web browing, computer based collaboration, searching dan data mining. Semua aktifitas itu bisa dilakukan dengan menggunakan web browser. Interface yang bisa dipergunakan untuk menjembatani terjadinya kolaborasi informasi ini selain web browser juga mailling list, forum diskusi, bahkan jika diperlukan aplikasi C/S (customer service). Adapun komponen yang ada dalam sistem untuk mensuplai terjadinya berbagai kegiatan tersebut meliputi database, web platform, data management tools, perangkat pengirim pesan, search engine, web service, document management serta interference engine.

Gambar 3 menunjukkan usulan gambaran umum konsep APTEKINDO knowledge management system. Sistem terbangun atas 4 pilar utama, yaitu teknologi, aktifitas, interface, dan berbagai komponen. Aktifitas yang diperlukan dalam sistem ini di antaranya web browing, computer based collaboration, searching dan data mining. Semua aktifitas itu bisa dilakukan dengan menggunakan web browser. Interface yang bisa dipergunakan untuk menjembatani terjadinya kolaborasi informasi ini selain web browser juga mailling list, forum diskusi, bahkan jika diperlukan aplikasi C/S (customer service). Adapun komponen yang ada dalam sistem untuk mensuplai terjadinya berbagai kegiatan tersebut meliputi database, web platform, data management tools, perangkat pengirim pesan, search engine, web service, document management serta interference engine.